Showing posts with label Cheese. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Cheese. Show all posts

Tuesday, March 15, 2016

Friday, March 6, 2015

Designing a warehouse event space out of pallets

|

| Adam's pallet construction studio. |

Adam Moskowitz owns the cheese importer/distributor/warehouser hub Larkin in Long Island City, Queens. (He's also the impresario behind the great Cheesemonger Invitational.) I visit his warehouse from time to time to taste incoming batches of Manchego for Essex St. Cheese. For most of the last year he's been outfitting a room as a teaching space. I've seen it grow from a typical concrete-and-cinder block slab to a warm, fantastic space. It's called Barnyard and most of it is decorated with parts of pallets that come with the cheese imports. Pallets on the lights, pallets as tables, pallets as chairs. Awesome idea.

Friday, September 26, 2014

Following Comté from Fromagerie No. 25 to Fort St. Antoine

Frutière a Comté des Hospitaux Vieux

Place de la Marie

The truck leaves at 3 am to collect milk from ten producers across three villages. Each farmer has about forty Montbeliard cows. This pickup run is called Ramassage. The old method, called La Coulée, where producers delivered

their own milk, is practiced by at just a few frutières of the thirty-four in the area. By AOC rules, the milk must be processed within twenty-four hours.

May is the big milk month.

Fromagerie No. 25, built in 1920, is run by one man, Sebastian Muller.

He makes twelve wheels a day seven days a week, using 1.6 million liters of milk per

year. It’s about average for a cheese maker that delivers to Marcel Petite, but small in the scheme of things. A big Comté fruitiere makes 5 times as much. The work for the

cheese maker, like that for cheese makers everywhere, is endless. Sebastian can

arrange for a few days off only if he reroutes his milk to another fromagerie, or

gets another cheese maker to substitute for him. He extended his wet arm for us

to shake. He works very fast, with few

words to us. He’s probably not used to company.

The milk truck is hooked up outside in the small parking lot

on the hill overlooking the valley. It has a long hose and the milk is pumped in.

Inside, where things are wet and smell sweetly ammoniated, the milk is

heated by a radiator and delivered to one of two big copper vats. Rennet is

added, curds form, and Sebastian cuts them with a rectangular wire mesh, kind of like a

big hard boiled egg slicer. This releases water. The temperature raises to 55 C,

drying and cooking the curd. When the curd passes the test—the cheesemaker puts his

hand in and no curd sticks to it—it's ready to pump overhead into the cheese molds.

Until now the curds have been treated gently. The next

process is brutal. A big vacuum hose lifts the curds ten feet in the air and

shoots them fifteen feet across the arched ceiling, unceremoniously plopping them in

one of four mold machines. Pressed for eight hours, held in their mold

until the next morning, they’re ulimately brought to “The nursery” where they

practice being cheese for three to four weeks, washed daily with morge, a brine made of water and the scraped crust of older cheese.

It’s the mother culture of the cheese maker, like a bread starter is to a baker,

one of the things that gives a cheese from a single fromagerie its unique flavor. The baby cheeses are—ironically bigger now then they'll be when they "grow up", since they lose water—are stored on spruce shelves, which the skin of comté enjoys as it turns to rind.

The shelves are rough cut, harvested when the sap has drained from them. You

can see thick, raw grains across the boards. That lets a little bit of air pass

under the cheese as it rests; wheels don’t stick.

Marcel Petite’s trucks visit every month to pick up young

wheels.

Fort Lucotte de Saint Antoine

“You feel like you’re coming to

the center of the cheese world: of industry, quantity, quality.”

Jason Hinds, Essex St. Comté

The road leads up through the

village, past some hills and a small forest. The fort is built underground, alone and invisible, marked only by a ten foot

tall door built into a hill. You park and enter by walking across a moat. The smell

is warm butter and pine. You’re ushered up to the lunch room first, for

espresso, the cheese halls flash by on your left. A few of the staff are

reading papers, eating cheese, drinking a 1998 Cotes du Jura, part of which has

found its way into a plastic water bottle. Windows open onto the Mont d’Or, leaves

umber and rust, but the grass is still very green. It’ll be that way until

first snow in December.

Cheeses arrive from the

fruitières regularly, 80% of which are in the mountains, along the Swiss

border. The hills were forested ten centuries ago, now cows graze on them. First stop is the top level,

La Maternelle, another nursery. Wheels are doused with sea salt to draw out

more water, washed with cool water to keep the “wrong” bacteria from being

active. Today there are about 25,000 wheels. They’ll stay there for 6

months when they’ll come down and join the 35,000 wheels in the lower

rooms.

Lights, camera—but nothing prepares

you for entering the Church of Cheese. The main room of the fort, once a covered

garden, holds 9,000 wheels of comté, each three feet across, seventy pounds, rising twenty feet high under a cathedral ceiling. The wheels look like rounds of wood or stone, in various stages of

growth, their surfaces sometimes smooth, other times mottled, molded, warty,

covered in patterns that look like lichen, rust, sandstone or bird shit.

Absolute silence, once in a while broken by the whir of little electric hand

carts. Or the lonely cheese washing robot that haunts the aisles. Little rooms are off to the side. They used to hold

52 soldiers each, now they store 900 wheels of comté.

I'm escorted by the affineur,

called the chef de cave Claude, and

his other half, Phillipe Goux, head of sales.

Claude is dressed in white jacket

and white hat, with nothing more than a note pad and cheese iron as tools. Mr Goux, born in Jura, eats comté two or times a day. He prefers younger cheese.

The fort has its own

micro climates. There are no heaters or humidifiers, just the bricks and the earth outside them. Grass grows in some areas. Claude taps, touches,

tastes. He’s trying to figure out where to send the cheese next. To the dryer

room? The warmer one? Much of his life is devoted to deciding what’s best for a

wheel, 60,000 decisions, one kind of cheese, endlessly repeated. Each wheel will only

be with him for a year or so but more will come. He’s developed a strange

coding system to keep track of each wheel’s journey. He scratches it the edge of

the wheel with his iron. A little window. A cross. Codes for him alone.

We taste thirteen cheeses. The routine is always the same. Claude walks

along the aisle, guided by the codes. He picks one wheel, tilts it out of its

cubby, rubs its top quickly, in circles. Tap tap tap the top, insert the iron on the edge of the wheel, turn,

remove. Smell. Pause. Take a piece, between thumb and forefinger, pass around.

Everyone follows, on cue. Take a bit of paste, warm it, replug the whole, use

the paste as a cement to seal it.

Dominic Coyte, Essex Street Comté’s selector, grades cheeses 1 to 5

for flavor, texture, longevity. Anything above 3 is fair game for him to buy.

Sometimes a cheese that was asleep a month ago comes alive. FIFO doesn’t work,

sometimes a November cheese is ready before an August. We don’t touch the

cheese, only taste. If Dom chooses a wheel Claude marks “ESSEX” on the

side with his iron.

The conversation is spare and clear. “I like it. It’s not

as dry.” Maybe it seems that way because of the language barrier; we’re English

speakers, they’re French. Maybe it’s because I’m with a bunch of Brits.

No 25. August 2005. Sweet. Full. Sour. Vegetal. Spicy at the

end. Meat. Roasted, especially onions. Cream. Nut. Cocoa powder. Caramel. Wet.

No 4, Oct 2005 Lovely. Nutty. Full mouth.

No. 7. September 2005. Dried prune. chocolate. Long flavor. Made by Christophe Parent in Narbief, Frutiere 747.

Marcel Petite, the man, started aging "just" 2,500 cheeses in 1966. He waged an uphill battle trying to change local cheese tastes from warm, fast-matured cheeses with big holes inside (like Swiss Cheese) to longer-aged cheeses with no holes, aged in cooler climates. Today Marcel Petite, the company, houses 60,000 wheels in Fort St Antoine, 80,000 wheels in another facility in Grenoble. Fort St Antoine, built in the late 1800s for the Franco Prussian wars, failed spectacularly when it deployed as part of the Maginot line in World War II. The French government sold it off, now it matures the country's best cheeses, most from the Jura's top fifteen mountain fruitières.

Wednesday, December 4, 2013

Friday, November 22, 2013

What do cheese and tuna have in common?

When I visited Spain last fall I had lunch with the brothers who own Ortiz, the source for our amazing tuna. They represent the fifth generation of the family running the company and they both grew up in the business. We ate at a seafood restaurant (naturally) and I remember the hake cheeks (!) we're really good, cooked in olive oil, scattered on a wide platter. The restaurant edged up to a walled, brackish tidal inlet that snakes through the town of Ondarroa, along the Bay of Biscay. Fishing boats were parallel parked along it. Across the water we could see the back side of the plant we'd just visited. It's Ortiz's oldest fish factory (they now have seven) and it's still downtown, right in the village, squeezed on main street between cell phone shops and cafes and hanging laundry. The family still maintains an apartment on the top floor.

Lunch was a bit rushed because we had to get to La Mancha that evening. We were going to see the cheese making at Finca La Solana, the farm that Essex Street Cheese Co. gets its Manchego. We were also going to taste batches of cheese to select for export. Batch selection is a process that was pioneered in its modern form by Neal's Yard Dairy in England. The idea is that, since cheese is made every day, every day is like a different vintage of cheese. Every vintage tastes different so you want to pick the best days. There differences result from different weather conditions, different food for the animals, a different starter and so on. With farmhouse cheese that's made naturally, all the variations add up to enough of an impact on flavor so that anyone can taste the difference between batches. I'm not exaggerating; I could bring you two different days of Manchego and no matter how much experience you've had tasting cheese I guarantee you would be able to taste a big difference between them. Companies like Neal's Yard Diary and Essex taste many batches of cheese and select certain days (called "makes") for their customers. In doing so they catch the high peaks of flavor when they come once in a while and avoid the off-flavor wheels. The results are cheeses that are more consistently better tasting.

When I described the cheese selection we were going to do one of the brothers lifted an eyebrow. He spoke some Basque to his brother (totally incomprehensible) and then told me that what we were doing sounded a lot like what chefs used to do with their tuna. When he was a young man he remembered them visiting the Ortiz factory to taste with his father and select a particular batch of tinned tuna they liked most. All the following year, whenever the restaurant ordered, only tins from that batch of tuna were delivered.

I asked them, "Does anyone do this any longer?" "No." "Could we do it?" "Sure."

I said, "See you next year!" as we bolted for the car. I've been excited about the trip ever since. Tomorrow I fly to Spain to taste this summer's and fall's tuna batches. More to come.

Wednesday, January 23, 2013

Recent Reading

A farm should be aesthetically, aromatically, and sensuously appealing. It should be a place that is attractive, not repugnant, to the senses. This is food production. A farm shouldn’t be producing ugly things. It should be producing beautiful things. We’re going to eat them. One of the surest ways to know if a wound is infected is if it is unsightly and smells bad. When it starts to heal, it gets a pretty sheen and doesn’t smell anymore. Farms that are not beautiful and that stink are like big wounds on the landscape.

From an interview with Joel Salatin, owner of Polyface Farms (he was the Virginia farmer profiled in Omnivore's Dilemma and Food, Inc.). Compellingly argued in ice clear language. From one of our country's great communicators on the problems with modern agriculture. Hat tip to Glenn.

That urinary tract infection? There's good chance it came from the chicken you ate. And it's getting increasingly antibiotic resistant because the chickens are taking antibiotics too.

Mitchell and Webb cheese fail:

Friday, October 19, 2012

Maria José

The only farmhouse raw milk unpasteurized unwaxed PDO Manchego in the world is made by a woman. Maria José's cheese is the best of its kind I've had.

Sunday, August 21, 2011

More Ways to Serve Cheese

What cheeses should you get for a cheese course?

Until a few years ago I’d answer that question with what I’d learned as an event caterer. Go with a variety: a young soft cheese, an aged harder cheese, maybe a blue, maybe a goat or sheep’s milk option. Two ounces per person. That is still a safe and delicious way to go.

Spending time with cheese mongers and makers over the last decade, I’ve experienced a few other ways to serve a cheese course that are fun, educational and rather tasty.

Progressions

Two or three versions of the same cheese aged for different lengths of time. For example, a young and extra-aged Comté. Or three different ages of Gouda. This is also great if you have different vintages of the wine from the same region.

Threesomes

Three goat cheeses: one fresh, one bloomy, one hard as a rock. Three blues. You get the idea.

Old World, New World

Try two clothbound cheddars, like Cabot from Vermont and Montgomery’s from England. Or a classic Swiss Gruyère and a cheese inspired by it, like Pleasant Ridge Reserve. Gouda from Holland, Gouda from Wisconsin.

One Giant Piece

I don't know exactly why but big cheese is way more fun than small cheese. Splurge for a four pound hunk of Parmigiano-Reggiano and stab it with the old, weird knife you've had lurking in the drawer for all these years. (Bigger chunks last longer so you can continue to gnaw on it for weeks.)

Cheese as Aperitif

Cheese to start dinner, like the cocktail and cheese hour our parents knew, is a more American way to serve cheese than the formal, end-of-dinner French way. Try kicking the evening off with an unusual pairing, like cheese with a salty anchovy or a couple salt packed capers, where the cheese becomes the sweet part of the experience.

Cheese Dessert

A sliver of Raw Milk Stilton with shards of dark chocolate. A small marble of aged gouda with a shot of espresso. If you’re serving dessert with sweet syrup, save some and drizzle it on the cheese.

This article appears in Zingerman's upcoming catalog Fall Food Buyer's Guide 2011.

Wednesday, March 2, 2011

Mountain Cheese Bloodlines

Mountain cheeses, no matter what country they’re made in, often share traits. They’re cousins, united by geography, climate and the techniques these harsh places demand. You can easily taste their bloodline connection.

Mountain cheeses can be big. In the hills among the Emme valley, two hundred plus pound wheels of Emmentaler, the original Swiss cheese, are produced. In the Jura region of France, northwest of Geneva, eighty pound wheels of Comté are turned out. Note that these are their finished weights, when they’re over a year old, after tremendous evaporation. When they’re first formed they can weigh up to fifty percent more.

Why are they so big? The answer, in large part, is winter. Mountain cheeses were traditionally a source of protein during cold months. They needed to be durable, they needed to last, since winter’s length was unpredictable. An eighty pound wheel of Comté will easily last until spring without spoiling. An eight ounce wheel of Camembert will not.

Mountain cheeses are sweet and floral. The sweetness is partly due to the bloodline process they share during making, where the curd is cooked. The floral aromas are thanks to the bloodline of the milk, which in the best cheeses comes from summer mountain pastures, called alpage in French. The L’Étivaz we sell is alpage. It is only made during summer, when the cows are in the mountains, eating an array of wildflowers the likes you and I haven’t seen since the Sound of Music. Imagine how good you’d feel if you ate flowers all day. That’s what happens to the cows. Their diet directly affects the flavor of the milk, which in turn flavors the cheese.

Most mountain cheeses melt beautifully, thanks to the curd cooking process. In spite of Courtney Love's advice to the contrary, I highly recommend it. Mountain macaroni and cheese is grand, and, grated on top of boiled potatoes and set under the broiler for a minute, these cheeses make a delicious bubbling cheese blanket. Try a Comté grilled cheese, made on buttered, griddled farm bread, with a grind of Tellicherry black pepper and maybe a couple thin slices of radish. If you have a vintage fondue set—available right now at your local Salvation Army for under a dollar, I'm sure—mountain cheeses are the ones you want to use.

Friday, February 25, 2011

It's time for my close up.

From a series of articles in the upcoming Zingerman's catalog featuring American cheese.

American Cheese Takes the Stage

Twenty years ago you could count the number of great American cheeses on two hands. Maybe that’s exaggerating, but not by much. Back then, being a small-scale cheesemaker was like being a beekeeper—a strange hobby, with little reward or recognition. Half the cheesemakers crafted nearly identical tiny wheels of goat’s milk cheese, which, given that we had no American goat cheese tradition to speak of, cheese shops insisted on calling chevre, the French word for goat. If you went into any serious cheese shop in America in 1994 chances are the only American cheeses you found were chevres and cheddars.

Have things ever changed.

At Zingerman’s Deli, cheesemonger Carlos now offers over a hundred American cheeses, almost half his total inventory. At the American Cheese Society’s annual conference judges had to wade through nearly 1,500 American cheeses to pick winners in 22 categories. In July, I attended a cheesemonger’s event in a warehouse in New York that had all the buzz and fun of an illegal, underground concert. It was packed with people watching other people cut cheese.

What has happened?

It’s impossible to point to one thing that’s given cheese such a spotlight. There is, however, a network effect among cheesemakers and cheesemongers that is different than any other I’ve seen in the food business. For the last two decades, dedicated merchants have educated a gang of cheesemongers. They’ve taught customers what good cheese is and how to buy it. The customers, in turn, have demanded better cheese. The cheesemongers have given feedback to the makers, who’ve improved their cheese. Cheesemongers and makers are thick as thieves. When I go to trade shows or food trips the cheese people all hang out together. They’re like a mafia. They have their own language and customs. They aren’t exclusive, though. Anyone can join. Just make or sell cheese, take it seriously, you’re in.

I give credit to our currency for the transformation, too. The dollar was relatively strong through the 1990s. It made great European cheeses relatively cheap to import. John Loomis, who made Great Lakes Cheshire—unsuccessfully—at that time told me, “Great imported English cheshire, made by people with decades of experience, retailed at $20 a pound. I was selling a local cheshire, made in Ann Arbor for 8 months, and it cost fifty percent more. I couldn’t compete. I quit after two years. But now, I started making it again, and with the British pound what it is, my cheese seems like a relative bargain.” That begs the question: what happens when the dollar rises again? It might make tough going for American cheesemakers.

What about the move to buy local? It certainly hasn't hurt. Many cheesemakers have found they can make ends meet just by selling at a few farmer's markets. (I've seen the same story unfold in England, too.) Still, if the the dollar gets stronger the cheesemakers will have the same problem John faced: experienced imported competition at low prices. At that point customers may be less concerned about having something nice and local and will look for something great to eat, something that makes them return to buy more.

Meanwhile, as eaters, all this is our win. We are in a golden age of American cheesemaking. Like Hollywood in the middle of the 20th century there is a glut of great talent. I just realized Oscar night is Sunday so — cheese and red carpet? Seems about perfect.

Saturday, November 20, 2010

Courtney Love says don't melt your cheese

"If you're gonna eat cheese, take it out on a picnic,

cut it up carefully, and really taste it—with wine or something.

Don't melt it on shit."

cut it up carefully, and really taste it—with wine or something.

Don't melt it on shit."

Courtney Love

Sunday, September 19, 2010

A Case for Trade: Learning from Each Other

The growth of good-tasting, small-production food in America—and parts of Europe—over the last decade has been great to witness. Eating here is so much better than it was twenty years ago. In restaurants alone the change is staggering. On recent trips to Italy I've found myself wishing I was eating pasta in New York, something that would not have occurred to me in 1990.

I’ve also seen several food making communities blossom where before there had been only large industrial operations. The number of small cheesemakers in the Northeastern U.S. and England has exploded. America’s Midwest is littered with excellent new artisan chocolate makers. So is most of Italy. Craft beer has had a solid run and craft distilling is coming on strong, especially in New York. Charcuterie and butchers are next. They have been growing in number, first in London, now New York and California. They will be headed inland.

This has all happened alongside a growing interest in locally made food.

To some extent it’s easy to think of the local food movement and international trade as opposite sides of the same coin. The perceived wisdom is that Local is small, worthy, good and environmentally sensitive. International trade is thought of as large, unsustainable, evil and environmentally harmful. I’ll leave most of those arguments aside for now (though I’d be happy to discuss them since many economists and food writers like Michael Pollan have shown that foods made farther away—those made in the best suited climate—can be more environmentally responsible than those made locally).

The case I want to make for trade is this: a lot of our excellent, local, American food wouldn’t be here today without trade. The expertise, the learning, the standards, the give and take—all were a product of trade. Great American food became that way as quickly as it did because we had superior food from other places to learn from and build on.

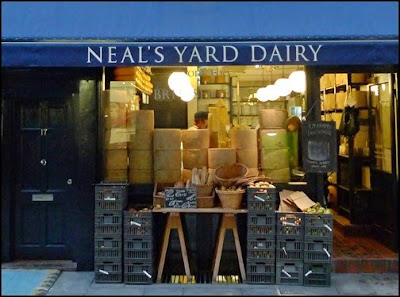

I’ll use one example from my own experience. Neal’s Yard Dairy is our London connection for handcrafted, farmhouse British cheese. They’re not just Zingerman’s connection, though. Many cheesemongers in America have visited them to learn how to do affinage (cheese aging), to select cheese, to learn their time tested processes. That has made American cheese shops much better. The cheeses that we import from Neal’s Yard have set a standard for excellence that has also inspired American cheesemakers. Many of them, most notably, Andy & Mateo Kehler of Jasper Hill have visited England to learn from the British, to design their new American cheeses and to build their own caves for aging and selection. Before Neal's Yard, American cheese was at a lower level. They're certainly not to be given all the credit for its revival and surge in quality. But to say they did nothing wouldn't be true either. They played a very meaningful part, especially through trade.

For me, trade and local are part of the same coin. Choosing local food doesn’t mean you have to opt out of the global economy. If you choose good companies to trade with, be they across the globe or next door, the food will be better and more sustainable. Great food companies, no matter where they are located, feed each other, teach each other, learn from each other and, if done right, make each other, and the world, better off.

I’ve also seen several food making communities blossom where before there had been only large industrial operations. The number of small cheesemakers in the Northeastern U.S. and England has exploded. America’s Midwest is littered with excellent new artisan chocolate makers. So is most of Italy. Craft beer has had a solid run and craft distilling is coming on strong, especially in New York. Charcuterie and butchers are next. They have been growing in number, first in London, now New York and California. They will be headed inland.

This has all happened alongside a growing interest in locally made food.

To some extent it’s easy to think of the local food movement and international trade as opposite sides of the same coin. The perceived wisdom is that Local is small, worthy, good and environmentally sensitive. International trade is thought of as large, unsustainable, evil and environmentally harmful. I’ll leave most of those arguments aside for now (though I’d be happy to discuss them since many economists and food writers like Michael Pollan have shown that foods made farther away—those made in the best suited climate—can be more environmentally responsible than those made locally).

The case I want to make for trade is this: a lot of our excellent, local, American food wouldn’t be here today without trade. The expertise, the learning, the standards, the give and take—all were a product of trade. Great American food became that way as quickly as it did because we had superior food from other places to learn from and build on.

I’ll use one example from my own experience. Neal’s Yard Dairy is our London connection for handcrafted, farmhouse British cheese. They’re not just Zingerman’s connection, though. Many cheesemongers in America have visited them to learn how to do affinage (cheese aging), to select cheese, to learn their time tested processes. That has made American cheese shops much better. The cheeses that we import from Neal’s Yard have set a standard for excellence that has also inspired American cheesemakers. Many of them, most notably, Andy & Mateo Kehler of Jasper Hill have visited England to learn from the British, to design their new American cheeses and to build their own caves for aging and selection. Before Neal's Yard, American cheese was at a lower level. They're certainly not to be given all the credit for its revival and surge in quality. But to say they did nothing wouldn't be true either. They played a very meaningful part, especially through trade.

For me, trade and local are part of the same coin. Choosing local food doesn’t mean you have to opt out of the global economy. If you choose good companies to trade with, be they across the globe or next door, the food will be better and more sustainable. Great food companies, no matter where they are located, feed each other, teach each other, learn from each other and, if done right, make each other, and the world, better off.

Saturday, August 28, 2010

You've Come a Long Way, Baby

Brooklyn, 2010

The American Cheese Society conference is this weekend in Seattle. Some of the best U.S. cheesemakers will be there and many of the most serious, dedicated cheesemongers. There will be hundreds of excellent, hand crafted, all-American cheeses to taste. Makes me think about how different cheese counters in the states looked twenty years ago.

In Brooklyn, of course, it can seem like another era on any given block.

Thursday, July 1, 2010

Cheesemonger Invitational

The first Cheesemonger's Invitational was held in Queens last Saturday. It felt like a culinary early 90's rave throwback, in part because it was Saturday and I was with hundreds of people in a remote warehouse. Also it was hosted by a former DJ (Adam Moskowitz), one of the judges was a former DJ (Jason Hinds) and at least one cheesemonger is a current DJ (our own Carlos Souffront). Plus there was music — from a DJ. (DJs seem to infest the cheese business like bike people do coffee.)

Ann Arbor did represent. I counted three of the nine cheesemongers with A2 connections. Anthea from Bi-Rite worked at Zingerman's. Matt from Rubiner's went to school in Ann Arbor. And Carlos is Zingerman's current and longstanding ace cheesemonger.

The competition ranged from cutting pieces to weight without a scale to identifying cheeses by taste. Congratulations to our man Carlos who pulled off third place.

Saturday, February 13, 2010

Behold the Power of Cheese

Last time I got punched in the eye protecting someone's virtue I put a raw steak on it. Now there's a vegetarian solution. Turns out I could have used cheese.

From the annals of awesome, here's an article on how Olympian Lindsey Vonn is treating her skiing injury with what amounts to cream cheese.

Monday, October 6, 2008

London, final notes.

Over three quarters of the cheeses for sale on the counter at Neal's Yard Dairy's are "new" cheeses. That is, non-traditional cheeses that have been made for the first time in the last couple decades. That surprised me. I expected a lot more of the counter dedicated to old traditional cheeses like Stilton, Lancashire, Cheddar. Instead there are lots of cheeses I'd never heard of a few years ago, like Ogleshield, Cardo and -- my favorite name -- Cornish Yarg.

Over three quarters of the cheeses for sale on the counter at Neal's Yard Dairy's are "new" cheeses. That is, non-traditional cheeses that have been made for the first time in the last couple decades. That surprised me. I expected a lot more of the counter dedicated to old traditional cheeses like Stilton, Lancashire, Cheddar. Instead there are lots of cheeses I'd never heard of a few years ago, like Ogleshield, Cardo and -- my favorite name -- Cornish Yarg.This mirrors what's happening in the USA. In the last five to ten years dozens and dozens of new cheese makers have started businesses. Other longstanding makers have become newly invigorated. In part I think some their strength is being derived from the weak dollar. European cheese costs a lot more than it did a few years ago. Next to a $35 per pound English Cheddar, American farmhouse cheese at $25 a pound looks like a relative bargain and more is certainly being sold because of price. But a lot of the success is thanks to hard work. When the dollar strengthens again we'll continue to have a much more diverse cheese landscape in America than we did before.

I think it's important to note that these cheeses might not have become great if it weren't for trade with Europe. There are simplistic arguments for local eating that miss out on the benefits everyone gets from trade. Because we can sell great cheese from Britain and Italy and elsewhere, because we developed a taste and awareness for this kind of cheese, because we created a market for greatness, we've built a foundation for great cheese to grow in America. U.S. farmers and entrepreneurs tasted, learned, and worked to make something as good as what Europe offered. Today a few American makers are creating cheese as good as you can eat anywhere. Imagine how much longer it would take if we had a closed market and we couldn't import these great cheeses to learn from? A bit of global trade helps local flavor.

I've added some photos from the trips to Montgomery's Cheddar and Linconlshire Poacher.

Thursday, September 25, 2008

Thursday, Montgomery's Cheddar

Cheddar was born in Somerset county, in south western England. Unlike Stilton, which protected its name, cheddar's name got loose in the world. It has been used to brand hundreds of copycats. But they're like shades of the original, haunting the edges of the earth. Today there are only three farms making traditional cheddar. That is to say, cheddar from a herd of cows located on same farm where it's made, unpasteurized milk, traditional animal rennet, hand-formed in 25 kilo forms, wrapped in cloth, larded, aged at least twelve months. They are Keen's, Westcombe, Montgomery's. I visited Keen's and Montgomery's, our regular cheddar.

Cheddar was born in Somerset county, in south western England. Unlike Stilton, which protected its name, cheddar's name got loose in the world. It has been used to brand hundreds of copycats. But they're like shades of the original, haunting the edges of the earth. Today there are only three farms making traditional cheddar. That is to say, cheddar from a herd of cows located on same farm where it's made, unpasteurized milk, traditional animal rennet, hand-formed in 25 kilo forms, wrapped in cloth, larded, aged at least twelve months. They are Keen's, Westcombe, Montgomery's. I visited Keen's and Montgomery's, our regular cheddar.Some jargon. Cheddar is the name of a cheese and the name of a particular process that makes cheddar what it is. After the rennet creates curds and before the curds are milled there is cheddaring. The mass of curds — a big, rubbery, gelatinous blob — is cut in the vat, stacked, flipped and stacked some more. The stacked weight, sloped against the vat, stretches the curd. It also squeezes out whey and increases acidity. When everything is right, an hour or two later, the texture of the curd is like cooked chicken breast. They're also very tasty, some of the best cheese curds I've eaten. It was hard to stop nibbling on them.

Some trivia. Montgomery cheddar cows graze on a hill that most scholars agree was the location of Camelot. I asked Jamie Montgomery, the owner, if that's true. With typical British dryness he replied, "Yes. We own Camelot."

Photos of a cheddar as it ages.

Next stop: London.

Wednesday, September 24, 2008

Wednesday, Linconshire Poacher

Brothers Simon and Tim Jones run their family farm in Lincoln- shire, on the eastern edge of England, near the sea. The ocean is so close you can see it from the last cow barn. Besides pheasants and crows, gulls occasionally fly overhead.

Brothers Simon and Tim Jones run their family farm in Lincoln- shire, on the eastern edge of England, near the sea. The ocean is so close you can see it from the last cow barn. Besides pheasants and crows, gulls occasionally fly overhead.Like many of the cheeses Neal's Yard Dairy sells, Poacher is relatively new to the world. A "new traditional cheese," as some like to call them. It has a lot in common with traditional English cheddar. The size, shape, color, and texture are similar. But it's made 350 miles east of the cheddar counties and it's got just enough other quirks to make it completely its own thing. Here it's pictured after it was washed, ready for boxing up and shipping out.

Simon, the agricultural college major, first started making Poacher in the early 1990's, about the same time that ZMO was born. Tim, his brother, the marketing and numbers guy, came on board in 1998, about the same time we started zingermans.com. Interesting symmetry there. We've been selling it at ZMO since 2006 or so, after our first visit to their farm. During that trip we tasted a great batch of thirty 45 lb cheeses -- a day's make -- and bought the whole lot.

We tasted about forty cheeses today, made on forty different days. There were a lot of good ones — it was hard to narrow it down! The finalists were all from 2007: March 21, April 27, May 30, July 20. Carlos, Grace and I settled on March 21, 2007. It's a savory-yet-sweet cheese with a full body that should last well into spring and summer of 2009. Look for it in late November.

Photos from Poacher.

Next top: Montgomery's Cheddar.

Tuesday, Stichelton.

When you arrive at the Stichelton cheese making operation at 7am, this is what you see. A twenty-five hundred liter tank of warm milk, just pumped a few hundred feet from the cow pen next door. The white stick on top is a paddle — for stirring by hand. Luckily there's not a lot of stirring to do. In fact, there's not a lot of anything to do. Stichelton is a cheese that takes a long time to make. Most of the time is spent waiting.

When you arrive at the Stichelton cheese making operation at 7am, this is what you see. A twenty-five hundred liter tank of warm milk, just pumped a few hundred feet from the cow pen next door. The white stick on top is a paddle — for stirring by hand. Luckily there's not a lot of stirring to do. In fact, there's not a lot of anything to do. Stichelton is a cheese that takes a long time to make. Most of the time is spent waiting.I keep saying Stichelton and you might be wondering "What is that?" Stichelton is the name cheese maker Joe Schneider and Randolph Hodgson of Neal's Yard Dairy (Joe's partner) have given to this cheese. In reality it's raw milk Stilton. They can't call it that in England since, there, proper Stilton can only be made from pasteurized milk (a rule that came into being a couple decades ago, though traditional Stilton had been made with raw milk for centuries).

This is Joe's third holiday season. (I say that because, like us, he thinks in terms of holidays. Stilton is the holiday cheese in Britain so he gets a big spike in orders then, too.) His cheeses are much better than they were in 2006, even better than 2007. He continually tests small changes to the recipe. The latest has been to use pre-ripened milk. He doesn't refrigerate the milk so its active cultures get a head start on making cheese. The results have been more interestingly flavored cheeses. Look for them in November.

Next stop: Licolnshire Poacher.

Tuesday, September 23, 2008

Monday, The Arches in London

I'm tasting and selecting cheese in England right now so I'll send some notes about what I'm learning.

I'm tasting and selecting cheese in England right now so I'll send some notes about what I'm learning.Monday. Went to Neal's Yard Dairy's Arches, where they store their selected cheeses and pack them for shipping. They're named The Arches because they are actually Victorian brick arches under the London Bridge-to-Dover rail line. The train rumbles overhead every few minutes. We tasted dozens and dozens of cheeses over a few hours. The process, if you've been part of it is: Plug the cheese with an iron that removes a long pencil of cheese, take a bit with your fingers, chew, think, write down what you taste.

The left side of this board was in front of shelves of Doddington. That's a big maroon-rind cheese we've carried once before. Each date is a different "make" batch. There are different comments about the taste and texture. "Creamy." "Flat" "Dull" And my favorite: "Corky" I agreed with their taster about the one at the bottom made July, 20 2007. It haslots of flavor." Seven wheels available. Carlos reserved one. We might, too.

Next stop: Stichelton.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.JPG)