The growth of good-tasting, small-production food in America—and parts of Europe—over the last decade has been great to witness. Eating here is so much better than it was twenty years ago. In restaurants alone the change is staggering. On recent trips to Italy I've found myself wishing I was eating pasta in New York, something that would not have occurred to me in 1990.

I’ve also seen several food making communities blossom where before there had been only large industrial operations. The number of small cheesemakers in the Northeastern U.S. and England has exploded. America’s Midwest is littered with excellent new artisan chocolate makers. So is most of Italy. Craft beer has had a solid run and craft distilling is coming on strong, especially in New York. Charcuterie and butchers are next. They have been growing in number, first in London, now New York and California. They will be headed inland.

This has all happened alongside a growing interest in locally made food.

To some extent it’s easy to think of the local food movement and international trade as opposite sides of the same coin. The perceived wisdom is that Local is small, worthy, good and environmentally sensitive. International trade is thought of as large, unsustainable, evil and environmentally harmful. I’ll leave most of those arguments aside for now (though I’d be happy to discuss them since many economists and food writers like Michael Pollan have shown that foods made farther away—those made in the best suited climate—can be more environmentally responsible than those made locally).

The case I want to make for trade is this: a lot of our excellent, local, American food wouldn’t be here today without trade. The expertise, the learning, the standards, the give and take—all were a product of trade. Great American food became that way as quickly as it did because we had superior food from other places to learn from and build on.

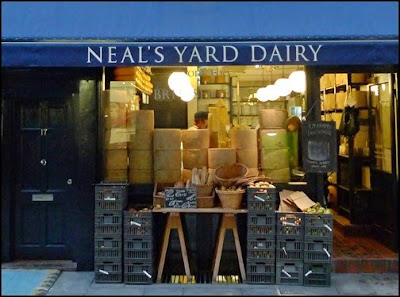

I’ll use one example from my own experience. Neal’s Yard Dairy is our London connection for handcrafted, farmhouse British cheese. They’re not just Zingerman’s connection, though. Many cheesemongers in America have visited them to learn how to do affinage (cheese aging), to select cheese, to learn their time tested processes. That has made American cheese shops much better. The cheeses that we import from Neal’s Yard have set a standard for excellence that has also inspired American cheesemakers. Many of them, most notably, Andy & Mateo Kehler of Jasper Hill have visited England to learn from the British, to design their new American cheeses and to build their own caves for aging and selection. Before Neal's Yard, American cheese was at a lower level. They're certainly not to be given all the credit for its revival and surge in quality. But to say they did nothing wouldn't be true either. They played a very meaningful part, especially through trade.

For me, trade and local are part of the same coin. Choosing local food doesn’t mean you have to opt out of the global economy. If you choose good companies to trade with, be they across the globe or next door, the food will be better and more sustainable. Great food companies, no matter where they are located, feed each other, teach each other, learn from each other and, if done right, make each other, and the world, better off.

I’ve also seen several food making communities blossom where before there had been only large industrial operations. The number of small cheesemakers in the Northeastern U.S. and England has exploded. America’s Midwest is littered with excellent new artisan chocolate makers. So is most of Italy. Craft beer has had a solid run and craft distilling is coming on strong, especially in New York. Charcuterie and butchers are next. They have been growing in number, first in London, now New York and California. They will be headed inland.

This has all happened alongside a growing interest in locally made food.

To some extent it’s easy to think of the local food movement and international trade as opposite sides of the same coin. The perceived wisdom is that Local is small, worthy, good and environmentally sensitive. International trade is thought of as large, unsustainable, evil and environmentally harmful. I’ll leave most of those arguments aside for now (though I’d be happy to discuss them since many economists and food writers like Michael Pollan have shown that foods made farther away—those made in the best suited climate—can be more environmentally responsible than those made locally).

The case I want to make for trade is this: a lot of our excellent, local, American food wouldn’t be here today without trade. The expertise, the learning, the standards, the give and take—all were a product of trade. Great American food became that way as quickly as it did because we had superior food from other places to learn from and build on.

I’ll use one example from my own experience. Neal’s Yard Dairy is our London connection for handcrafted, farmhouse British cheese. They’re not just Zingerman’s connection, though. Many cheesemongers in America have visited them to learn how to do affinage (cheese aging), to select cheese, to learn their time tested processes. That has made American cheese shops much better. The cheeses that we import from Neal’s Yard have set a standard for excellence that has also inspired American cheesemakers. Many of them, most notably, Andy & Mateo Kehler of Jasper Hill have visited England to learn from the British, to design their new American cheeses and to build their own caves for aging and selection. Before Neal's Yard, American cheese was at a lower level. They're certainly not to be given all the credit for its revival and surge in quality. But to say they did nothing wouldn't be true either. They played a very meaningful part, especially through trade.

For me, trade and local are part of the same coin. Choosing local food doesn’t mean you have to opt out of the global economy. If you choose good companies to trade with, be they across the globe or next door, the food will be better and more sustainable. Great food companies, no matter where they are located, feed each other, teach each other, learn from each other and, if done right, make each other, and the world, better off.